Steven Volk, Co-Director, GLCA Consortium for Teaching and Learning, Professor of History Emeritus, Oberlin College

January 14, 2019. Contact at: svolk@oberlin.edu

NOTE: This is cross-posted at After Class.

On January 10, 2019, the Great Lakes Colleges Association/Global Liberal Arts Alliance (GLCA/GLAA) Consortium for Teaching and Learning offered a Webinar on “Syllabus Preparation.” You can access a recording of the hour-long presentation and Q&A here. (Please note that there were some audio difficulties at 25:45, but it only lasts for some 40 seconds.) The Webinar was partially based on ideas from this article. Finally, the slides that were used for the Webinar can be accessed separately here.

From: From 114 proved plans to save a busy man time (A.W. Shaw Co, 1918).

A “syllabus,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “(a) a concise statement or table of the heads of a discourse, the contents of a treatise, the subjects of a series of lectures, etc.; a compendium, abstract, summary, epitome,” and, in a more contemporary sense “(b) a statement of the subjects covered by a course of instruction or by an examination, in a school, college, etc.; a programme of study.” We all know it as the “thing” (I believe that’s the formal term) that we need to have completed by the first day of class. Perhaps instructors dislike it so much because when we finally copy it for distribution, it means that our summer/winter/whatever break is over. (I’m old enough to associate the smell of the mimeo machine ink with the start of a new semester.) And, perhaps, instructors dislike it because we don’t think our students will actually read it. We certainly have ALL had occasion to answer a student’s question by responding, “It’s on the syllabus!”

And yet – I will argue – the syllabus is actually a critical document whether or not your students read it (and I will suggest ways to get them to, yes, read it). Why is it so important? It is the actual place where your understanding of learning theory (how students learn) intersects with your pedagogical style and approach (not just what you feel comfortable with, but what you understand as important for student learning) mapped out on the field of reality: the content that you have to “cover” that semester, how well your students are actually prepared, and the concrete reality of your life at that moment (new child at home? a parent who is ill? a book manuscript due at the publisher? your “heavy” teaching load semester, etc.). What I am arguing is that a “successful” syllabus – one that helps you teach and bolsters your students’ learning – needs to take these elements into account. Yes, you can prepare a syllabus that is close to the original Latin meaning of the word: a list – in this case of the readings and assignments. But to do so is to lose the opportunity to grapple with what you really want to accomplish in your course and how you can help your students achieve at a high level.

As I noted, the syllabus is a strange animal: conceivably the most important (and complicated) teaching document you will prepare each semester and yet a document that most students will only use to find out what they’re supposed to be reading that week or when assignments are due.

The root of the problem is that the syllabus is really two different documents serving two different purposes. On the one hand, for students, it has become a quasi-legal contract that sets out what they must do to complete the course successfully as well as your responsibilities to them. On the other, it is the most comprehensive guide that you will prepare detailing how you plan to organize a body of information in such a way as to reach your educational goals while having the greatest impact on student learning. To the extent that the syllabus is only about the first purpose, it is as interesting as a “End User License Agreement” document that you sign when you download a new piece of software. Yes, it needs to be explicit and unambiguous, but besides detailing your responsibility to your students and their obligations to you, it should also indicate everyone’s responsibility to course learning. More important to the success of the course is the second element, which is often either missing or implicit in the syllabus. My recommendation: make it explicit.

Syllabus as Contract

Since it is the first purpose that often gets the most attention, I’ll turn to it first. The syllabus traditionally serves as a contract setting out rules, regulations, and expectations: when assignments are due, how they will be graded, what is allowed and what is prohibited. To the extent that faculty want to use the syllabus-contract to cover every eventuality, from policies on laptop use in class to the rules for acceptance of late papers, the contractual part of the syllabus can take a lot of space and, often, become both intimidating and unwelcoming. “Welcome to the class: Here’s a long list of what you can’t do and what you’ll be penalized for!” Ugh.

Since it is the first purpose that often gets the most attention, I’ll turn to it first. The syllabus traditionally serves as a contract setting out rules, regulations, and expectations: when assignments are due, how they will be graded, what is allowed and what is prohibited. To the extent that faculty want to use the syllabus-contract to cover every eventuality, from policies on laptop use in class to the rules for acceptance of late papers, the contractual part of the syllabus can take a lot of space and, often, become both intimidating and unwelcoming. “Welcome to the class: Here’s a long list of what you can’t do and what you’ll be penalized for!” Ugh.

Still, the contractual part of the syllabus is important and thinking it through clearly can help you avoid headaches down the line. (Kate Susman, a biology professor at Vassar, offers some additional useful advice on the syllabus as a contract.) The syllabus divides the course into weekly, daily or other units, informs students what they are responsible for in each session, when assignments are due, where they can find required readings, where they can get help, and how to contact you, as well as college policies on academic integrity, accommodations and matters concerning class conduct.

This is the part of the syllabus where you can be specific about requirements/recommendations that can help students by being quite clear as to expectations:

- The syllabus should detail how students can get in touch with you (office address, phone, etc.) but you should also indicate the best way to contact you (text message, email, etc.) and when you will be “off-line” (E.g. “I shut down all electronics at 9:30 PM, so don’t expect a reply from me until the next day.”)

- You will note due dates for your assignment (E.g. Tuesday, Feb. 5), but if you want them in before 11:59 PM, note it on the syllabus: “Assignments are due at the start of class on Tuesday, Feb. 5.”

- Be clear about mark-downs for late assignments: Do you subtract a grade step for each day late? Will students think that means each class day late as opposed to each calendar day? You can make it explicit with an example: Papers due on Feb. 5 that would have gotten a B+ will get a B if turned in on Feb. 6, a B- on Feb 7, etc.

- Explain how students will be evaluated. Build in opportunities for low-stakes feedback and scaffold assignments carefully. Explain how final grades will be determined. Clarify how grades will be weighted or if you grade on a curve.

- Let students know what materials are required and where they can buy or access them. If you are assigning a specific edition of a text, include the ISBN number so as to avoid confusion.

This section should also include anything that your college or university requires you to state, such as your policies on accommodations, honor codes, accessing course materials, etc.

Brown’s Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning includes some other things to keep in mind:

- Use accessible, inclusive language. Students may not yet be versed in your field, so avoid unnecessary jargon and technical terms (what I call the “secret handshakes” of academia) that some students might not understand. Make sure your syllabus (and your course) is accessible to students from diverse backgrounds and does not inadvertently make some feel excluded.

- Set the right tone. As I noted above, think about the learning environment you want to create in your course and use your syllabus to help you do this. Consider whether you want to include language on preferred gender pronouns in the syllabus. Try to avoid writing a syllabus which is largely a list of things that students can’t do in your class.

- Clarify the kinds of academic support available. Make sure students know about campus resources that support their learning.

The Learning Syllabus

But it is the second, often invisible or unwritten, part of the syllabus, what has been called the “learning syllabus,” that is more important both for you, the instructor, and ultimately for the students. As teachers, we develop a set of goals and objectives for every course, and the syllabus should not only state these goals clearly, but embody them in the basic design of the course. The goals set out what we want our students to have accomplished over the time they are taking the class. To be sure, we want them to master a body of knowledge, become more skilled in a variety of ways, develop a greater awareness of themselves as individuals, members of a group, and as thinkers. The syllabus is both the road map guiding your students to achieve these goals (and therefore it needs to describe your responsibilities toward the students: i.e., this is what I will do to help your learning) and the yardstick you will use to measure whether they have met the goals: i.e., this is what you, as a student, must do to succeed in the class. (And, when the course is over, if you find gaps between your expectations and the students’ success rate, you will want to think about ways of changing the course when next you offer it.)

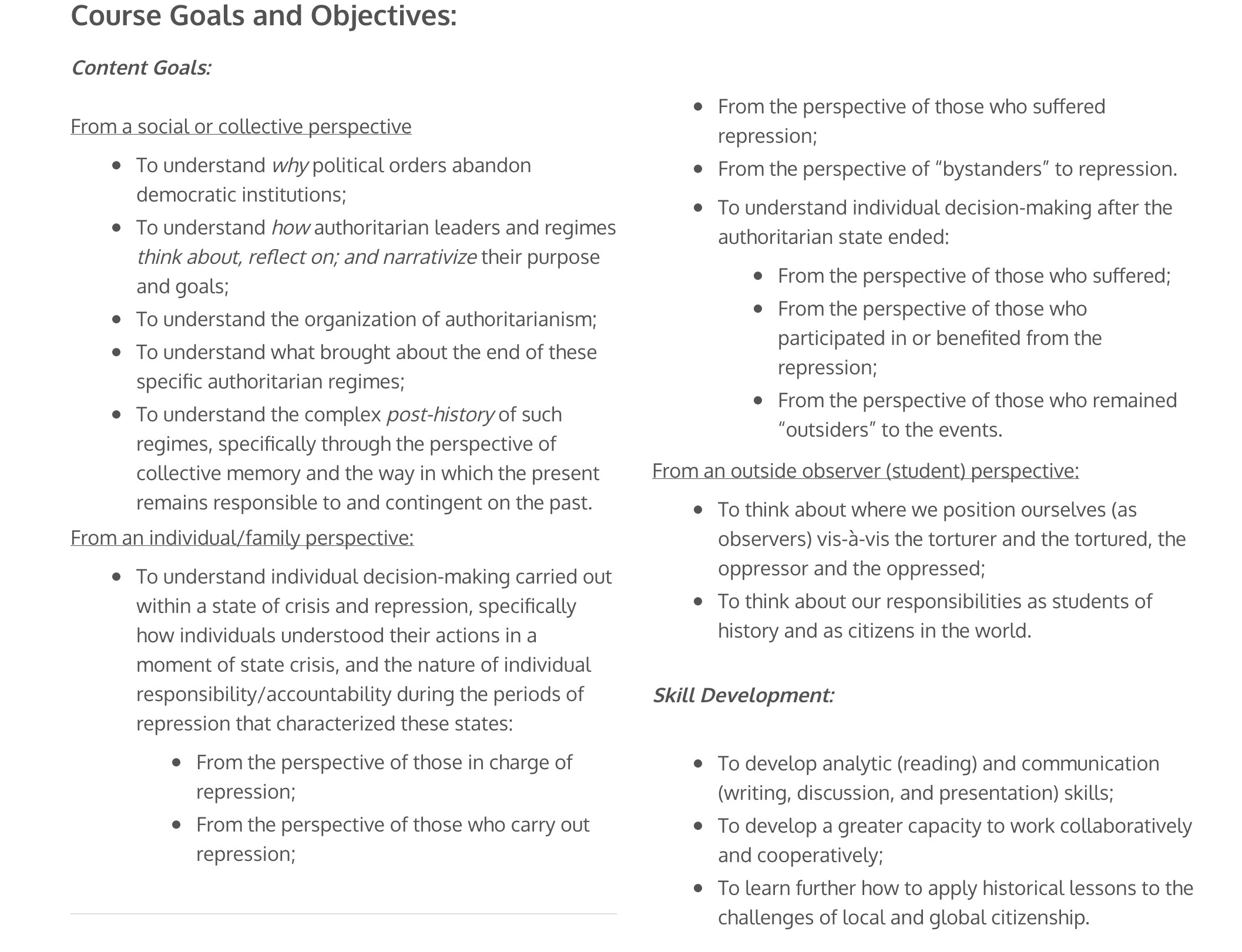

From Volk, History 293 (Dirty Wars & Democracy), Fall 2015

A good way to approach the syllabus, then, is to start at the end, with your course goals and objectives. Backward planning is a central concept in learning design. It suggests that you start with where you want your students to be at the end of the course (what they should know, be able to do better, have thought about, etc.). I modify that somewhat and imagine what I want my students to have retained from the course some ten years after they took it. I have found this to be an important exercise in thinking about student learning, particularly as we observe that in the digital age so much information is available instantly on one’s smartphone that memorization is even less important than it once might have been. Concepts, approaches, and skills have become so much more important.

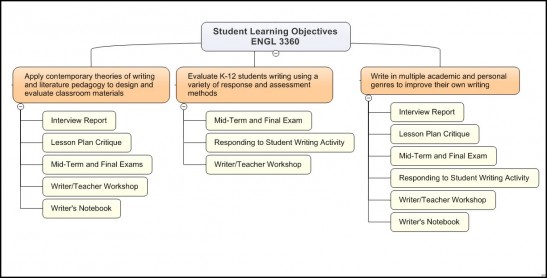

With your goals specified, the next question is how you will know if the students have met them. So, once you have set your learning goals, you need to think about assessment. For example, if one learning goal is the ability to analyze and evaluate conflicting secondary sources and you only give exams in which memorization is the key component, you will have a hard time assessing student learning vis-à-vis your goals. Assignments – your assessment tools – need to flow logically from goals.

Image: Billie Hara’s English 3360: https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/graphic-display-of-student-learning-objectives/27863

But how can you assure that your students are best prepared to succeed in meeting your final goals and that these goals are scaffolded appropriately, moving from easier to more difficult tasks, providing opportunities for recovery after failure? Perhaps one of your goals is to develop greater skills at collaboration. We know that our students will have to collaborate productively if they are to succeed when they leave school. How do we best prepare them? If collaboration is one of your goals, but the only activity you have that requires collaboration is a co-authored final research paper, it’s quite likely that many will not succeed. Collaborative writing is difficult, and unless students have more low-stakes practice at it, they will have an unreasonably hard time with that final project. Go back over the syllabus and find those occasions where you can insert more group work, opportunities when the students can write short, non-graded collaborative memos, etc.

With your goals determined and your assignments properly scaffolded, you can then go back to the task of determining which content best fits into which week and how that builds on the learning from the previous week.

Cottenet’s Villa. New York Public Library Rare Book Division, 1860. Public domain.

The thought that goes into your syllabus, the architecture that supports learning in your course, will often remain hidden from the students. What they see are the contractual elements and their weekly obligations. Because of that, I have always found it useful to make explicit what is hidden, both on the syllabus and in the course itself. Write your learning goals into your syllabus; link your assignments to your goals, indicate why that assignment is scheduled when it is, what its purpose is at that moment, and how it will help them achieve the course goals. Continually engaging students with the underlying structure of the course helps them both understand the work that went into preparing it and what its goals are beyond the transfer of knowledge. We know that students, even if they have read the syllabus, will soon forget it – so remind them of the architecture of the course when you write assignments and explain them in class.

Flexibility

Can you change the syllabus over the course of the semester? It depends. There are certain “contractual” items that you change only at a certain risk, and definitely not without a class discussion: moving assignment due dates earlier; adding previously unassigned readings or assignments, etc. At the same time, syllabi aren’t iron cages and if you find that you have planned in something that actually gets in the way of learning, definitely talk to your class about changing it. I will push assignment due dates back, telling the class why I’m doing it (often because I haven’t finished grading the previous assignment and the feedback is important if they are to do better on the next assignment). Further, even after years of teaching, I still assign too much reading. If I find that the volume of reading gets in the way of the learning that we, as a class, are trying to accomplish, I will make certain required readings optional instead. Always discuss syllabus changes with the students so they understand your perspective as to why they have been changed. But don’t be trapped by your own syllabus.

(Public Domain)

You can also take “syllabus flexibility” into other areas as well, particularly those that invite student co-participation in the construction of the class. Some faculty will wait until the first days of class in order to write parts (or even all) of their syllabus (the “blank syllabus” approach) with input from students. This might involve selecting readings from an anthology or a larger set of potential readings, creating a unit – complete with readings and assessment – that they don’t find on the syllabus and think should be added, designing the assignments and selecting due dates, etc. Inviting students to develop codes of conduct for the classroom, which will then be written into the syllabus, is another way of encouraging students to take responsibility for their own learning, as are different grading forms such as contract grading (also here and here), or self-grading.

All this said, two caveats are in order:

- Students, of course, are taking more than your course, and they often have planned their classes carefully, with an eye to assignment due dates. If you change the due date to a later one, it might impact the work they have to do at that time. For that reason, I always tell students that they are free to hand in their assignments on the originally scheduled date and to see me if they need additional instruction (or feedback from earlier assignments) that will help them with this one. (Needless to say, very few students have taken me up on the offer and turned in their assignments on the original due date!)

- I have heard from a number of students with learning disabilities, particularly those on spectrum, that they rely on the stability and fixed nature of the syllabus and changes can become both upsetting and difficult for them to accommodate. For that reason, it’s best to discuss the matter with the students in question and to get more informed advice from your own learning specialists.

Paper or Digital

This brings up the question of whether to distribute paper syllabi or put your syllabus online. Most colleges and universities require us to provide students with a syllabus for the course, but that can be either in paper or online. Many faculty have moved to online syllabi as a way of saving paper, permitting easy and direct links to online materials (required readings, audio and video files, other websites, etc.), allowing instructors to make alterations in the course as it evolves, and – if you so desire – sharing your syllabus with the wider world. There are numerous web-building sites (with WordPress being among the most popular), for example, as well as one’s own Learning Management System, that can allow you to develop an attractive online syllabus with no technical skills. (If building a digital site, make sure that it is fully accessible to students with disabilities.)

I have found that one of the advantages of putting my syllabus online has to do with aesthetic values. If the syllabus is a document that we want our students to actually read, it helps that it is visually attractive. You can do this with paper syllabi as well, of course, but the online medium is more accommodating to the aesthetic syllabus.

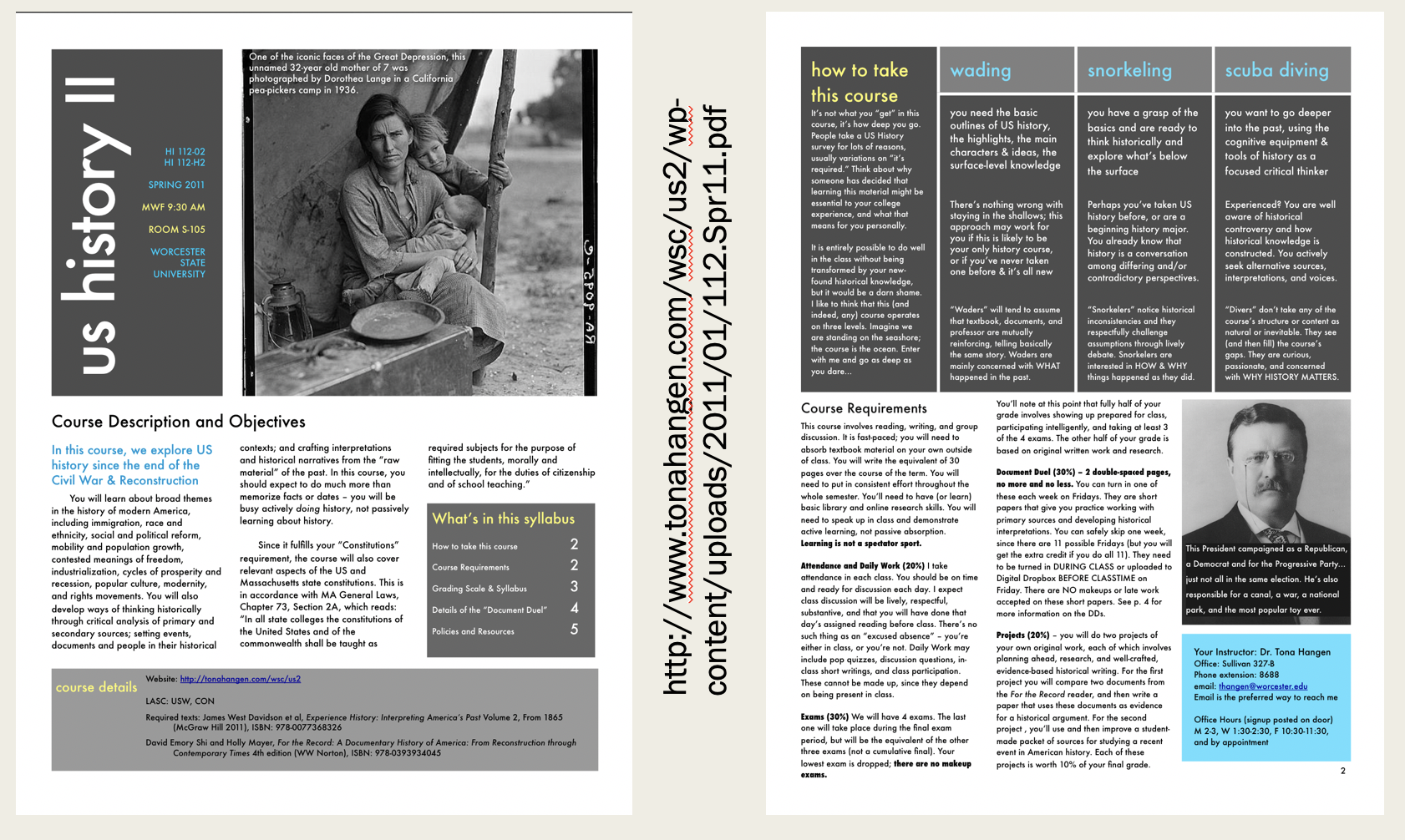

From Tona Hangen’s US History II course at Worcester State University: http://www.tonahangen.com/wsc/us2/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/112.Spr11.pdf

If You Build It, Will They Come? When to Hand Out the Syllabus

Will students even read your syllabus, now that you’ve put so much work into it? In terms of the more “list-like,” contractual elements – no. But you can do things to encourage them to read the syllabus, and to return to it at various times over the semester. Some of this has to do with when you hand it out.

Most faculty, I would hazard a guess, hand out their syllabi at the beginning of the first class, and then go over them page by (sorry!) boring page. I would suggest that rather than doing that, hold off distributing it until the end of the class. Instead, get students engaged with the subject matter. Tell them why you have spent your professional career studying your subject area. Or, if you plan on creating an active learning environment, get them talking – to each other and to the class as a whole. The pattern you set on the first day – whether silently listening to you or actively engaging in discussion – often sets the tone for the rest of the semester.

Towards the end of the class hand out the syllabus, go over anything they need to know for the next class, and tell them to come to class – having read the syllabus – with one question that they have about the course, one aspect of the course that most excites them, and one aspect that they are the most worried about. Collect them at the start of the second class and go over them later to inform yourself about what they are interested in and whether there are any aspects of the syllabus that they have found confusing.

Some faculty will use images in their syllabi which they ask students to study and will gear discussions around them over the course of the semester. I’ll often ask students to think about their own learning goals for the course in relation to my goals and to write a paragraph on what they hope to accomplish in the course (outside of learning the content). I collect these (with the students’ names on them) and then hand them back at the end of the semester when I ask them to reflect on what they have learned and whether they met their learning goals.